The one on the right is the gas.

The one on the right is the gas. Pacing

No story is all action or all leisurely contemplation—or at least none worth reading. It’s vital to keep your story moving forward, but not relentlessly and not always at speed. Likewise, you must allow your characters to stop and think, but not to the point of putting your reader to sleep. A book that consisted of nothing but gunfights and car chases might be fast-paced but would soon become as boring to read as one where characters sipped tea and chatted about literature for 300 pages. People in fiction, like people in the real world, don’t always live life at the same speed, and readers need a break from both too much laid-back navel gazing and too much break-neck action.

There are two easy ways to check up on your pacing as you edit yourself.

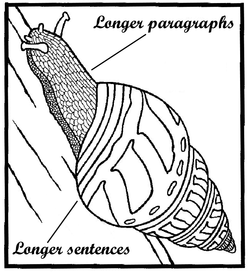

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 17

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 17 Count the words in a few dozen sentences from different parts of your work. Do they vary in length? Sentence length variety does at least two good things: it changes up the rhythm of your writing, and it helps control the pace.

Count the words in the sentences of an action or dialogue sequence, and do the same for a more leisurely part of your story. Which part had shorter sentences overall, and which longer? If there wasn’t much difference, you might need to work on tightening up the pace of your faster-moving scenes.

Long sentences tend to slow the pace of a story. There are times when you want to do this, particularly just before or just after a sequence of fast-paced action. In a slow-paced scene, sentences can lengthen out just a bit. Think of it like a heartbeat. When everything’s peaceful, the story’s heart rate can be slow and easy until the next action moment.

Thomas watched the gulls wheel in the gray sky above the gray water, always seeming to be on the lookout for whatever might be down there just below the surface. He threw the last of his stones into an incoming wave and walked back up the shore toward Lena’s place, more than half hoping no-one would be home yet.

Average length of a sentence: 29.5 words.

When the action picks up, so does the heartbeat. Pick up the pace of narrative with shorter, punchier sentences that contain less observation and reflection and more action and/or dialog.

Two figures resolved out of the mist. Thomas dropped behind a sandbar, heart hammering. It was Dexter and Clarke. Lena’s mother must have told them where he’d be.

Average length of a sentence: 7 words.

Dialogue is a form of action, and one that can move a story forward rapidly.

“Those two could have killed me. If they’d seen me, they would have.”

Mrs. Flores wrung her hands in the dish towel. “I didn’t tell them anything!”

“You’re the only one who could have!”

“No, Thomas, I never talked to them. I swear!”

“Leave her alone, Thomas,” Lena said. “She didn’t tell Dexter and Clarke where to find you.”

“Then who?”

“I did.”

Average length of a sentence: 5 words.

Let the length of your sentences help create the pace of your narrative and signal the reader how much forward movement to expect as soon as they see the page.

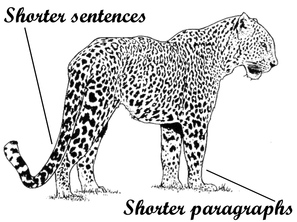

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 18

The Fiction Writer's Coloring Book, Fig. 18 Alternating the length and action content of your paragraphs is a good way to slow down and speed up pacing. Long paragraphs slow the pace. This can be a good thing in moderation, but when a reader sees lots of lengthy paragraphs ahead, she may begin to skim. This is a slippery slope that might end with her putting down your book and forgetting to pick it up again.

Conversely, short paragraphs, including dialog, tell the reader that the pace is picking up, along with the information-to-words ratio.

When reading drags, break up long paragraphs into two or more. Use dialog and other short action paragraphs to slow down reading speed and perk up reader attention.

Part of the Matthew Scudder series.

Part of the Matthew Scudder series. Pace is also determined by content, so if your sentence and paragraph length matches the pace you’re hoping to set with your words, you won’t be working against yourself in that regard. It can be useful, however, to go against the reader’s expectations for pace. Let me give you an example of how a master does it.

Near the end of Everybody Dies, one of the Matt Scudder novels, Lawrence Block puts two well-loved characters in an unbearably tense situation. As they walk across the countryside into what they know is a trap to face an unknown number of well-armed men, the reader knows that one man is here out of loyalty to the other, who has foreseen his own death. In point of fact, both are far more likely to die violently and soon than to live past the next few minutes. Many authors would have made sure to speed up the pacing to keep the reader glued to the page, but Block has another way of snagging hearts and minds; he uses the time it takes them to walk to their fatal rendezvous to have one of the characters talk about life, his past, his philosophy, his beliefs. With every paragraph that delays the coming shoot-out, the reader is gripped by apprehension and anticipated grief. When the deadly shoot-out finally happens, it’s almost a relief to have the waiting over with.

Where Block could have sped the reader on to the final confrontation by upping the pace, he made the tension unbearable by slowing it. Where he could have written a perfectly fine chapter, he wrote a masterful one. Pace is but another of the little toys excellent writers like Lawrence Block use to keep readers buying and reading and anticipating books.

Chances are you'll fall naturally into keeping sentences and paragraphs at the proper length for the pace of your scenes, but if a scene isn't working, it may be worth reading to see whether or not the pace you need matches the pace you've written. I'll talk about how language choices affect pacing and other aspects of your writing in next week's article, "Two Languages."

TL;DR

Sentence and paragraph length directly affect story pacing. In general, they get shorter as the action speeds up, longer as it slows down.

Reading pace is to some degree the opposite. As pace picks up, reading rate slows down. As pace drops, reading speeds up.

Vary the length of paragraphs in slower-paced sections to keep readers’ eyes from glazing over.

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazing Pulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Thanks for linking to this article!

Regan Wolfram's Speculative Fiction Writing Wroundup

Mystery Writing is Murder

A Novel Experience - Best of the Week's Articles

Did I miss anyone? Let me know!

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 7: Two Languages

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Part 9: Dangling Modifiers

Part 10: Passive Voice

Part 11: Homophones

Part 12: Point of View Violations

RSS Feed

RSS Feed