You are a veritable genius.

You are a veritable genius. Two Languages

Writers of English have extra linguistic resources, owing to that fact that English is two utterly distinct languages more or less happily married into one language of incredible richness. When a word from one branch won’t do, we can always go looking for one belonging to the other. The trick is to know which language to employ in which circumstances.

Linguists everywhere consider English to be a Germanic language, but less than a third of today’s language actually derives from Anglo-Saxon roots, most of the rest having come to us from Latin, either directly from Roman influence or from Romantic languages such as French, a bit from Greek, even less from the Celtic language of the Britons who were running England when the Romans arrived. In a language race, the conquerors always win.

Conquest and language enrichment our speciality.

Conquest and language enrichment our speciality. So that’s how we got here. The question for our purposes seems to be “How does having a dual language affect us as writers?”

Thanks for asking.

English is hard work, and thirsty to boot.

English is hard work, and thirsty to boot. For all that Anglo-Saxon doesn’t measure up in terms of actual numbers, most of the words it does provide are the most common in the language. Most everyday words for the common things and actions of everyday life are still based in English’s Germanic roots. One does not generally perambulate with one’s canine as often as one walks the dog. In a normal day, we are more likely to eat food than to consume or devour victuals, sustenance, or comestibles. Our language is two-thirds Latin, but our common usage is overwhelmingly rumpled old Anglo-Saxon, dressed in faded jeans and moccasins (no socks). When Latin comes out to play, it does so wearing its best clothes.

Okay, not THIS simple.

Okay, not THIS simple. For the purposes of ordinary, everyday fiction writing, and even most nonfiction writing, the plainest flavor of English is almost always the most unnoticeable and unnoticed, and writing that doesn’t call attention to itself for its own sake is writing that communicates its intentions clearly. When it’s time to make a reader see, hear, taste, smell, or feel something, the language needs to get out of its own way, and that happens when you keep it simple.

It’s usually better to say

- Used than Utilized

- Started than Initiated

- Before than Prior to

- So far than As of yet

- But than However

- Rest than Remainder

- Found than Discovered

- Happened than Occurred

Not all of those pairs involve Latinate English vs. Anglo-Saxon, but they do concern wordy and elaborate vs. clear and unadorned language. The more decorative word or phrase will be needed far more rarely and usually when you’re looking for a more formal style, deliberately distancing the reader from the narrative, or making your language sound educated, self-important, unemotional, or wordy. That’s what Latin-based English does best.

Latinate language puts the brakes on pace.

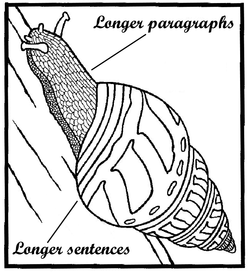

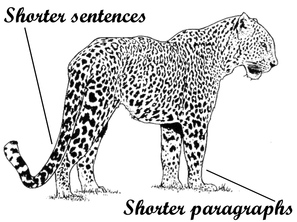

Latinate language puts the brakes on pace. The type of language you use helps to set the pace of your writing. Longer words, which are most often of Latin origin, help slow pace down by removing the reader from the immediacy afforded by more direct language. Shorter words, most often Anglo-Saxon derived, help speed it up. This is also true of dialog; when their feet are to the fire, characters tend to use the shortest, punchiest way to say anything. If you choose to have them do otherwise, do so deliberately and for good reasons.

Choose and Use

Speaking very generally, Latinate English is cool, erudite, perceived as higher in status and educational level, emotionally muted, and detached. Anglo-Saxon English is warm, down-to-earth, perceived as lower in status and educational level, and emotionally present. In real life, we tend to switch to Latinate English when we want to distance ourselves from the listener or establish higher status, and to shade over into Anglo-Saxon vocabulary when we’re going for closeness or establishing ourselves as "just one of the folks."

Most English speakers know unconsciously how to modulate their usage of Latin-based vs. Anglo-Saxon words depending on situation and context. We go back and forth between one and the other dozens of times every day, but most of us have never given the distinction a lot of conscious thought. Knowing about our two languages gives us a powerful tool for flexible and effective writing.

TL;DR

Rule of thumb: Anglo-Saxon English is informal, direct, close. Latinate words are the opposite.

Prefer use over utilize, start over initiate, happened over occurred, before over prior to.

Keep it simple except when you don't. And when you don’t, know why you didn’t.

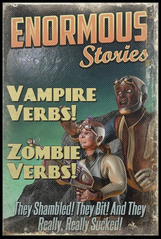

COVER ART

All the fabulous pulp magazine covers on this article series were created using the amazingPulp-O-Mizer from art by its creator, Bradley W. Schenck.

Thanks for linking to this article!

Regan Wolfram's Speculative Fiction Writing Wroundup

A Novel Experience - Best of the Week's Articles

The Book Designer's Carnival of the Indies #35

Did I miss anyone? Let me know!

Part 1: The Most-Hated Writing Advice Ever

Part 2: Vampire Verbs, Zombie Verbs, and Verbs that Kick Ass

Part 3: Attack of the Adverbs!

Part 4: The Weakeners

Part 5: When Words Get in the Way

Part 6: Secrets of Relative Velocity

Part 8: Dialogue Tags

Part 9: Dangling Modifiers

Part 10: Passive Voice

Part 11: Homophones

Part 12: Point of View Violations

RSS Feed

RSS Feed